Han Shan temple

During a trip to China in September 2015, Kritee (Kanko) had the tremendous good fortune of being able to meditate at the Han Shan Temple in Suzhou, the home temple for our Rinzai-Obaku Zen lineage; and meet their leading priests.

As an introduction to Zen practice in China, we note that it was similar to the Japanese form. However, Chinese Zen practice has differed, historically and existentially, from Japanese Zen practice. For centuries Japanese priests have come from priest families, which are supported by the communities in the neighborhood. In China, before Cultural Revolution, all priests depended entirely on charity, and they took vows of celibacy, like Buddhist priests in many other parts of Asia. At the moment, Chinese priests are supported by the government and are apparently under government regulations. For his book “The Practice of Chinese Buddhism 1900-1950”, Holmes Welch researched temples all over China and found that meditation was a big and integral part of the temple activities. At this time, there are discontinuities in meditation schedule at many temples which were primarily created by the Cultural Revolution which erased the cultural memory of how to practice in the proper way. Lay people in China and Japan do not practice much, in the past or now; and nobody ever thought of allowing non-priests to practice in temples until beats showed up at Japanese Zen temples.

Han Shan temple is believed to have been founded during the Tianjian era (502–519) of the reign of Emperor Wu of Liang, who is fabled to have questioned Bodhidharma about the essence of Buddhism. It was originally called Miaolipumingta and the current name of the temple derives from Han Shan, the legendary monk and poet, who along with his disciple-poet-friend Shide (pronounced Shir-duh) is said to have come to the monastery during the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang (627–649). At present, the temple covers an area of about three acres and since its latest reconstruction in 1906, it presents the architectural style of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) (please click on individual photographs to be able to see high resolution images and their description).

In addition to the Great Hall and the hall of four heavenly kings, the temple has a five- story four-sided pagoda, several small grotto- like structures made of natural lake sedimentary deposits, stelae (stone tablets), courtyards and buildings, stupa and sculpted thangkas, bells, monks’ residential quarters, areas for offering incense and tying red ribbons, and shops. At the time of this visit, there was only one large legendary bell onsite (not two as mentioned in several online resources). In keeping with the principles of traditional Chinese architecture, every other building except for the pagoda emphasized horizontality as opposed to the height or depth of the building. All temple walls were painted in yellow, the imperial color.

Entrance: The entire complex is guarded by a large entrance gate with three doors. This gate leads into a long corridor where walls on both sides are lined with stelae (stone tablets) where poems from various Chinese poets are inscribed. At the end of the corridor lies the famous Maple Bridge which diagonally faces the wall marking the entrance into the temple.

Front Hall of four heavenly kings: As is typical of East-Asian Buddhist temples, you enter through the hall of Four Heavenly Kings or Devas (gods), the Guardians of the Four Directions. At the front of this hall, there was the joyful future Buddha, Maitreya Buddha, known to the Chinese as the “Laughing Buddha” with his fat paunch. Directly behind the Laughing Buddha, separated by a wall, was the statue of the great warrior Deva (god) Wei-to, the Protector of Buddhist temples, faith, books and (according to my guide) hungry people. Clad in full armor and holding a scepter-shaped weapon resting on the ground, he is considered to be a general under the command of the Four Heavenly Kings. He is always supposed to face the Great (Mahavira) Hall, which was separated from the front hall by a courtyard.

Courtyard between Great Hall and Front Hall: This large courtyard hosted a space to light incense, an enormous rectangular burner to receive the incense and also a tree where visitors can tie red prayer ribbons (When Kangan, my teacher’s teacher visited the temple in 1980, such signs of religious activity were not allowed in China). It also hosted a small single-story pavilion. Closer to the Great Hall, on the left, were sculpted thangkas and sculptures of lions, dragons and elephants.

Great (Mahavira) Hall: In a traditional East Asian temple complex, the Mahavira Hall (literally: “Hall of the Great Hero”) is the main building. It is there that Gautama Buddha and other bodhisattvas are enshrined. This hall is called a hondo in Japanese. On both the east and west walls of this Great Hall, one could see the figures of the nine arhats (Buddha’s disciples) who supposedly possess various kinds of supernatural powers. Meditation in China is done sitting full lotus on a small tilted stool (see two stools at the end of photograph showing nine arhats), and with shoes on! The rubbing (inscribed paintings) of Han Shan and Shide actually dates from the T’ang Dynasty.

Courtyard between Great Hall and Founder’s Hall: There was a gift shop on the right, and moon-gates and red lanterns on the way to Founder’s Hall. There was also a small room on the left with what appeared to be a large beautiful ink painting of Damo (Bodhidharma) between a painting of Han Shan and Shide, as well as a black stone tablet, this time with carved images of Han Shan and Shide.

Central (Founder’s) Hall: To honor the founders of the temple, the third hall housed golden statues of Han Shan and Shide. While some temples have a meditation or teaching hall associated with the central hall, none was observed in this temple at the time of this visit.

Large courtyard between Central Hall and Pagoda: A very large white tablet housed in a pavilion with golden calligraphy done by the former abbot, named “Nature of Sky” (性空), in the center. A hallway along the sides displayed many stelae with poems written in white letters on black stone. The temple library on the left faced a very large incense burner and a bridge with a water fountain. One couldn’t easily find a meditation hall in the temple, and so Kritee meditated in front of library. The library housed a magnificent ink painting of a lion (see photograph below).

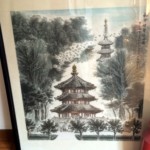

Pagoda: A pagoda is a tiered tower with multiple eaves and is found in many Asian temples. In Sanskrit, the word “pagoda” (or stupa) meant a “tomb.” Pagodas were originally built for the purpose of preserving the remains of Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism. Eventually, the pagodas also starting serving as shrines or monuments. At Han Shan temple, out of the pagoda’s total of five tiers (floors), only two were open to the public. The roofs were supported by dougongs (Chinese brackets). The top of the pagoda was marked by a metallic finial.

Courtyard between pagoda and a gift shop: This courtyard housed a stele (tablet) inscribed with an entire poem by a Tang Dynasty poet Zhang Ji. Behind this stele was a wall housing a larger black relief covering the entire width of the wall with carvings, apparently depicting stories from Buddha’s life. There were two large octagonal lamps on each side of the Zhang Ji “poem tablet.” There was also a large souvenir/gift shop between this courtyard and the last one.

Last courtyard: The last courtyard housed what we believed to be one of the two 108 ton bells which are supposed to belong to the temple. (In Buddhist tradition, 108 is the number of perfection.) The courtyard also enclosed a natural structure called “Guanyin Peak” with corridors on all four sides. The legend has it that the tolling of the two bells was the way that Han Shan and his disciple-friend Shide could communicate their deep affection for each other when they were separated.

Meeting with Han Shan priests: There hadn’t been a way for us to inform the temple residents about our likely visit but on the second visit to the temple complex, we hoped to meet local shopkeepers (including Xia Lu, a talented calligrapher and ink-painter) in the hope that they might know about “Nature of Sky,” the retired former abbot whom Roshi Kangan Glenn Webb had met in 1980, or about the meditation schedule at the temple. While meandering in the area, we chanced upon a sprawling building which turned out to be the Culture Research Institute of Han Shan Temple. As she was admiring large scrolls of calligraphy mounted in this building, Mr. Yao Yan Xiang (President of the Institute) arrived, introduced himself and welcomed us to explore the entire building. Mr. Xiang presented us with two of his latest books and a long calligraphic note which described the teachings of the temple. Upon seeing the short letter in Chinese (see below) that described the connection between Han Shan temple and our sangha in the US, and the photograph of Roshi Kangan Glenn Webb with the former abbot (Nature of Sky), Mr. Xiang summoned the vice-abbot of the temple as the current abbot Qiu Shuang was out of town. While we could not communicate in English, there was a subtle joy in having found each other. Everyone confirmed that the previous abbot (“Nature of Sky”) is now 94 years old, doesn’t speak much but can sometimes comprehend what others are saying. The vice-abbot was happy to note that the Han Shan lineage had traveled to US and inquired about the details of our community in New Jersey and Boulder. The two men also had Kritee pose with the scroll of Diamond Sutra (Vajraccedike Prajna Paramita Sutra) which they had been taking along with them during their travels in Asia as they spread their teachings. They kept the letter Kritee had brought along (see below for a shortened version of the letter in Mandarin and a detailed description of Kangan’s visit in English here) for presentation to the abbot upon his return.

您好!我可否拜见方丈?我的禅名是寒光。我是一个在美国生活的禅师,拜寒山寺的宗派。我的师父是个美国人,他的本名叫科特斯麦尔,禅名寒感。他生活在美国新泽西州,主持一个僧伽,称为“寒山禅”,网址(http://coldmountainzen.org/)。 我住在美国科罗拉多州,在那里我主持一个小的禅修团体。网页是(https://boundlessinmotion.org/).

寒感的师父名叫寒巖(意思是寒冷的岩石)。寒巖曾在1980年左右来到苏州寒山寺。寒山寺方丈接待了他。方丈的名字叫性空。方丈给了他如下一卷字。静、中、知、秒的意思是玄机、深奥、不可知。方丈还在此卷左右两边题字,肯定了我师父的师父寒巖传承寒山寺宗派,是唐代禅师兼诗人寒山的佛门弟子。方丈在卷中写道:今天美国而来的僧兄拜访我们,他建立了德岩寺。我们欢迎他来到苏州以及他的宗寺。我们祝福他。”