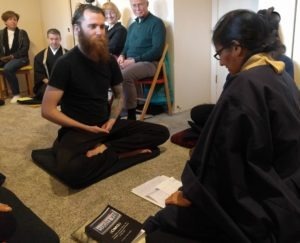

Jukai (Lay ordination)

(From Aidan Kankyoku) On December 8th, 2019, the last day of our Rohatsu Zen sesshin I celebrated an important rite of passage called Jukai (the formal initiation into the Zen Buddhist way, also called Lay ordination). In this ceremony, a Buddhist Zen practitioner openly receives and acknowledges the sixteen bodhisattava precepts as an ongoing path in their lives. This is something I have been preparing for for more than a year directly, and for almost 6 years indirectly, since I first began practicing Zen. In another sense, I’ve been preparing for it my whole life.

As my teacher Kanko Sensei explained, Jukai is a Japanese word with two characters. The second, pronounced Kai, refers to the precepts or vows, 16 vows one must undertake to enter formally into a Buddhist lineage. The first character, pronounced Ju, in this case means “making space for.” The ceremony and the process leading up to it represent a commitment to make space for these vows in my life and to continue to evolve my understanding of them, as they are far from simple.

For the year leading up to the ceremony, I worked to develop a nuanced understanding of sixteen Bodhisattva precepts (sometimes referred to as vows) with Kanko Sensei. I also sewed a Rakusu, the ritual bib like garment for which I collected scraps of discarded fabric from important teachers in my life, including Hunter Ewen, Yoko Hiraoka, and my mother. Then I sewed the Rakusu by hand. It took about 50 hours! I’ve never sewn anything before so there was a pretty sharp learning curve. (Some people don’t sew from scratch but rather get pre-cut pieces and the process can be faster. The purpose of sewing practice is to slow down and bring intention to our lives.)

In the ceremony, Kanko Sensei spoke about the history of our lineage, which goes back teacher by teacher directly to the historical Buddha, as do all Mahayana lineages. Some of the records of our lineage have been lost forever, but the teaching lives on.

I began working Kanko Sensei after years of floating and searching for a teacher who had what I needed. The way that she holds and presents the Dharma, or teaching, is radical and unlike anyone else I have heard. With this rich Dharma, she has challenged me in ways I never imagined.

I began working Kanko Sensei after years of floating and searching for a teacher who had what I needed. The way that she holds and presents the Dharma, or teaching, is radical and unlike anyone else I have heard. With this rich Dharma, she has challenged me in ways I never imagined.

After sharing about the history of our lineage, Kanko read the vows one by one asking me to repeat them after her. The first three are vows to take refuge in the Buddha, the enlightened being each of us truly is, as well as the Dharma, the teaching of the historical Buddha as they are taught today, and the Sangha, the community following those teachings. The next three are the “pure” precepts, thus called because they get straight to the point: do not create evil, practice good, and really, really practice good.

The final ten offer a bit more guidance on what that might look like, though in truth, we find they raise more questions than they answer. Altogether there are sixteen Bodhisattva precepts.

Before accepting my commitment, Kanko Sensei prodded me on the meaning of these vows to remind me of their non-dual nature. She asked questions ranging from easy (if ICE came knocking on my door and there were undocumented folks inside, would I lie; yes) to the agonizingly difficult (if she herself were desperately ill, and only I could help her, and only by taking the life of an animal, would I do it; I had to answer honestly that I do not know).

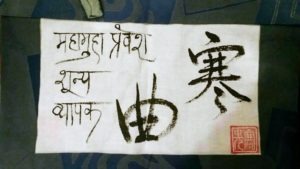

Next, Kanko revealed the calligraphy she had placed on the back of the Rakusu. The beautiful calligraphy in Kanji was done by my Tea ceremony (Chadō) teacher Yoko Sensei. Traditionally, this calligraphy has two parts. The large characters are often for the student’s new Dharma name, a name carefully chosen by the teacher to honor a special part of the student’s path. The name Kanko chose for me is pronounced Kankyoku. The first character, Kan, means Cold. It is the first character of our lineage name, 寒山, Cold Mountain, and everyone in our lineage takes Kan as their first character. Cold is a euphemism for enlightenment, but make no mistake, adopting this name in no way means anyone attains perfect enlightenment. We don’t believe such a thing exists, at least not in the popular sense.

The second character, Kyoku, means melody, sound or musical composition. My musical practice has been an integral part of my Zen journey, and sound (or its opposite) have formed a basis of my personal relationship with the Dharma. So my new name is Kankyoku, or “Cold Melody”. The second part of the calligraphy is a teaching, also chosen uniquely for the student. This Rakusu is unique in having the name in Japanese, but the teaching in Hindi. In fact, this teaching does not come from Zen at all, but from Vinoba Bhave, Gandhi-ji’s spiritual heir. Looking at the meaning, however, one would never know it came from outside zen: In Romanized hindi, it would read “Mahaguha Pravesh Shunya Vyapak”, a poetic minimization of a quote in Sanskritized Hindi from one of Vinoba’s many books “महागुहा में प्रवेश : बाहर से व्यापक; अंदर से शून्य”. The full quote means “Enter the Great Cave: From the outside, is vast and endless; From the inside, it is empty/zero.”

I cherish the multilingual nature of these gifts as an artifact of my practice with Kanko sensei. Zen has been a vital bridge between two otherwise isolated parts of my life, my activism and my art/music life. For me, the Japanese roots of Zen as it is practiced in the U.S. today holds the artistic impulse of the teaching. It was in Japan that Zen was fully developed into a complete cultural force, spinning off a radically unique way of creating music, art, poetry, and dance, as well as creating entirely unique aesthetic rituals such as Tea Ceremony, or Chadō.

I cherish the multilingual nature of these gifts as an artifact of my practice with Kanko sensei. Zen has been a vital bridge between two otherwise isolated parts of my life, my activism and my art/music life. For me, the Japanese roots of Zen as it is practiced in the U.S. today holds the artistic impulse of the teaching. It was in Japan that Zen was fully developed into a complete cultural force, spinning off a radically unique way of creating music, art, poetry, and dance, as well as creating entirely unique aesthetic rituals such as Tea Ceremony, or Chadō.

On the other, Buddhism’s (and Kanko sensei’s) Indian roots holds the socially engaged impulse, from the historical Buddha’s radical campaign to subvert the caste system of India, to Gandhi’s historical innovations in applying the ethic of Nonviolence to social struggle (Kanko’s maternal grandfather was a freedom fighter with Gandhi) and his rival B.R. Ambedkar’s revival of Buddhism again as a way of subverting caste. This Rakusu thus symbolizes the unity of these two impulses in my own Zen practice.

After revealing the name and teaching on the Rakusu, which was unknown to me until that time, Kanko placed the Rakusu on my shoulders, marking my formal entry into Cold Mountain lineage. It was an unexpectedly multicultural ceremony. Trinley, who is ordained in the Kagyu Repa tradition of Milarepa, surprised us by leading us through a Tibetan prayer of rejoicing, and Tendai priest (and dear friend) Shōnen-san performed a Dharani, bringing in a diversity of Buddhist traditions.

I love the above picture with my mom, on the far left, watching.

I love the above picture with my mom, on the far left, watching.

Shōnen-san, in the middle, shared a warning as he was reminded of his own precept ceremony: ‘this is where the hard part begins, as the precepts will start to poke you in ways you never expected.’ At first, I didn’t think much of this comment. It’s not as if I have been waiting until today to start abiding by these vows. I have been turning to them for guidance for years.

Yet even the first 24 hours after the ceremony vindicated Shōnen’s wise words, and each passing day continues to do so. I’ve gone through a series of misadventures which have in different ways put my understanding of the precepts to the test and showed how much growth is still needed (and will always be needed).

It is clear to me now that Jukai marks much more of a beginning than an ending. It marks the beginning of a lifelong pursuit of “practicing good” via the meaning of what seem at first to be simple, black-and-white vows. So I’m asking my dearest friends and loved ones to help me in this process by holding me to account. I have a sea of gratitude to my mom Julie Stapleton as well as Shōnen, Ateret, and Imtiaz for bearing witness along with 8 friends from our growing Sangha. But I’m asking anybody who loves me and cares about my mission in the world to bear witness as well, starting with these photographs, and continuing into my conduct in the world whenever it crosses into your perception. If you see me straying from these vows, please be loving and firm with me. Remember that I am giving everything I have to help create a less violent world, far too important a mission to allow me to repeat the same mistakes over and over again. And if you ever want me to return this tremendous gift, merely say the word.